Last week, Devin Taylor and I met with six of the top managers and supervisors at Denton Municipal Electric. It was incredibly gracious of them to give us two hours of their time in the evening when they could have been home with their families.

They knew about our op-ed, in which we expressed doubts about their proposed Renewable Denton plan. They came very prepared to field our questions. I will do my best to share some of the things we discussed here. If Devin or members of DME find errors here, I will incorporate them with updates.

To be candid, much of the conversation was so technical that I couldn’t grasp it well – what with forward markets and power purchase agreements and all that.

So, I pretty much listened in as Devin (who is freakishly intelligent) debated the details with DME’s top executives. It was fascinating. It was the kind of “trial of strength” that I wished this plan had been subjected to more publically and earlier on.

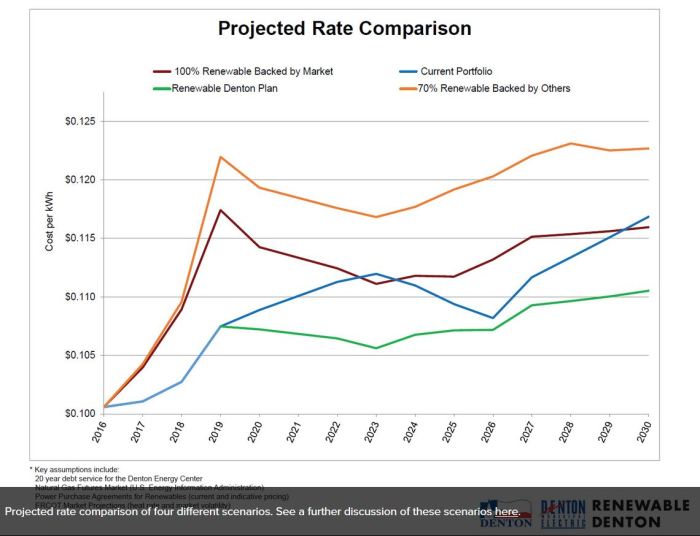

For me, the most telling moment came when we got talking about risks. They handed us a graph from just the day before that showed electricity prices spiking for about twenty minutes from the usual $30/MWh all the way up to $1,000/MWh. It turns out that almost none of the wind power forecasted for that day (by predictions made just the day before) showed up. The conversation went something like this (reconstructing as best I can from memory – not direct quotes).

DME: See, this is why we need a quick-start back-up plant…to shield us from these kinds of market swings.

Devin: But by the time you start up the gas plants that spike would have already gone down.

DME: No, we can get these things fully operational in just a few minutes with very little start-up costs.

Devin: Ok, but such a short swing like this looks scary but averaged across the whole day it pretty much washes out. It might be like $1 extra, or mere pennies for a rate payer.

DME: Ok, but if a pipeline were to freeze (as happened a few years ago) or if it is summer and a nuclear plant goes down, then a spike like this can be even higher and it can last for hours or days…even weeks.

Devin: But what is the likelihood of that happening to such a degree that it actually costs more than the money you’ll be putting into these power plants?

DME: Who can say? But we have an obligation to deliver reliable and affordable electricity to our customers. We cannot expose ourselves to that kind of risk…

Devin: Of course, there are also all sorts of risks in investing in a technology dependent on a volatile fuel. Have you considered this or that [things Adam can’t quite grasp]?

DME: Yes, we did consider this and that and it turns out that what we have proposed is the best path for maximizing renewables, minimizing rates, and minimizing risks to reliability.

(I am reminded of Councilman Gregory’s response to our op-ed: “You think DME hasn’t thought of all this stuff?!” Yes, clearly they have, but I think it is important for the thinking to be more public in nature…remember how the public helped DME find a better route for a transmission line several years ago…)

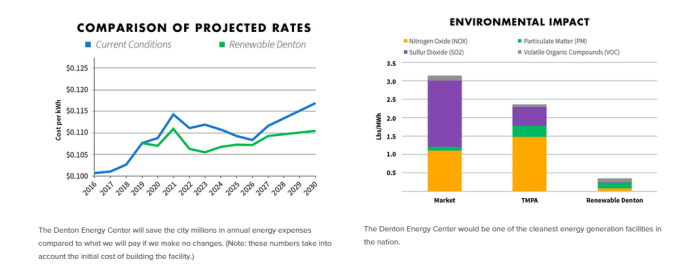

That’s when they described the gas plants as analogous to a life insurance policy: “The best case scenario is that we never run these plants, because that means we are getting cheaper electricity on the market.” They also said that something like 90% of the value of the gas plants is in the fact that they allow us to make long-term power purchase agreements for wind and solar. In short, their value is that they take the risk out of a major investment in intermittent electricity sources.

There was a wrinkle in the life insurance analogy, though. Because, as Devin noted and I think they agreed, actually the best case scenario is that we get our wind and solar cheaply, but market prices are above the cost of running the gas plants. In that scenario, we can run the gas plants at full capacity (I think that is something like 37% of the time) and sell electricity on the market for a profit.

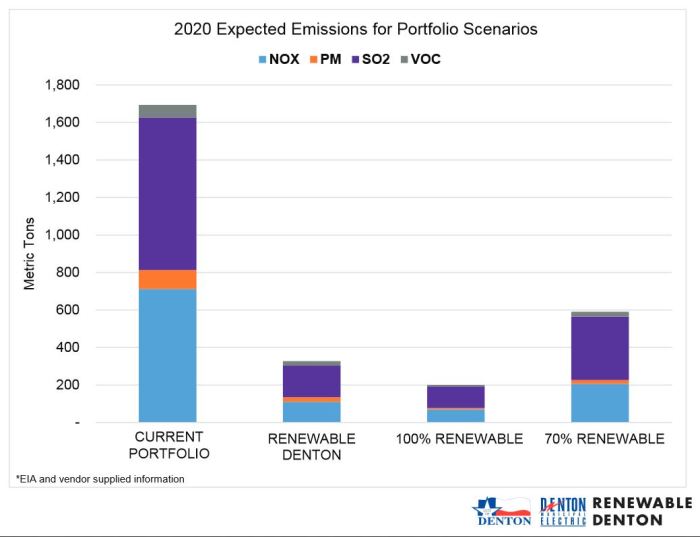

We then talked about the environmental impact of the gas plants. One of the interesting claims they made there was that they won’t contribute to local ozone pollution, because ozone tends to form a bit further from the point of emission once it mixes in the atmosphere and heats in the sun for a while. So, these plants would likely exacerbate air quality downwind from Denton more than in Denton. But, of course, in the scheme of things these are very efficient plants with lower emissions than anything comparable on the Texas grid. Incidentally, they use a mere handful of gallons of water to operate, whereas other gas plants use millions of gallons of water.

The future of Gibbons Creek coal plant is still undecided, they said. My thinking on this is that if the Renewable Denton plan moves forward, we will no longer use it but it will probably stay operational. However, I think that means that some other dirtier and less-efficient source of electricity will be squeezed out of the market. As we shift our demand to more wind and solar, we open space for others to use Gibbons, which is surprisingly a better environmental performer than some other coal plants.

A couple of other points are worth noting. First, they claimed that in addition to ending our use of coal, the plan will entail the construction of between 2 to 4 new wind farms and 2 to 4 new solar plants. And, second, the hope is that they can soon start working on constructing community solar power projects (which would be in addition to the ones just mentioned) on the extra land surrounding the gas plant sites. They are also hoping that battery storage technology improves such that they might use some of the land for that purpose in the future.

They are definitely keen to get to even more renewable energy – they just don’t think that the 100% renewable option right now is a prudent one from a cost stand point.

This is a decision that obviously entails lots of technical stuff. Yet woven into all of that are values and interpretations. For example, just how risk adverse should we be? And of course it is laden with uncertainties. For example, I don’t think we can know the overall environmental impact of this plan because it is so open ended – we may add more renewables (when?) and we’ll burn more or less gas depending on market conditions.

I don’t know how I would vote if I were on City Council. I just talk myself in circles on this issue. It sounds like the clock is ticking, though – interest rates and exchange rates are favorable but perhaps not for long. A decision is likely imminent.

For now, though, there is still time for questions. I look forward to the discussion next Tuesday at the public hearing.